A remarkable thing happened while working on my latest novel, Grand Theft Octo. I wrote about 500 words that needed almost no editing whatsoever. Although I didn’t splurge them out in a carefree frenzy, I didn’t write them especially slowly either. They took about an hour. There were a few places where I had to ponder and a couple of lines that tripped me up but somehow I managed to write about 500 words that required almost no editing whatsoever in an hour. If you’re not a writer yourself, you might wonder why that’s a big deal, but for me it was a miracle. Let me tell you why.

Writing is Rewriting

People say writing is rewriting. Writing is the fun part whereas the real skill and effort comes during editing and rewriting. A lot of this depends on the way someone writes. Some people edit as they go whereas others bash out a first draft before editing it later. Either way, editing and rewriting is the largest factor in the quality of prose. Most first drafts are full of clichés and humdrum phrasing. They almost never shine. Although you’ll occasionally get lucky and come up with a great line on the fly, most of the real gems come later.

You wouldn’t want to live there

Editing is a skill you hone, a muscle you develop. There are books to help you on the way but for most authors it’s self-taught. When I first started writing as a child, I thought everything I wrote was a masterpiece. Even if I re-read a story, I couldn’t spot a single thing to change. Criticisms from my teachers seemed absurd. I assumed they were biased or too stuffy to recognise my dazzling skill. The more I wrote, however, the fussier I became. I’d take more time with my sentences and ponder over the story instead of splurging it out. Nevertheless, writing was a joy. Each story I wrote was like an adventure. I’d polish them the best I could and looked forward to my future as a world-famous author.

Welcome to the Skill Plateau

When I was a teenager, after two abandoned novels, I started on another. That’s when I hit the plateau. I scrutinised every single word, trying to make each sentence perfect. I tried to inject subtext, metaphors and hidden meanings to subconsciously influence the reader. I wanted every description to paint a picture so vivid that the reader would see a realer world than the one outside their window. I avoided every cliché, I ran from every trope. And at this pace, I managed to write a sentence an hour. That’s not an exaggeration. The first (and only) chapter of my third (abandoned) book took six months to write. I re-read it not long ago and although it has some inventive language, it’s clearly over-laboured and bordering on pretentious.

For my next book, I tried to limber up. I didn’t want to make the same mistake. The problem is, I’m a perfectionist. Only the best would do. Although I managed to work quicker, my next book took three years to write. I only managed to get it finished by drinking 4 litres of Diet Coke every day and staying up to 6am. With that book, I’d bash out a chapter in a couple of days and then spend a month or two editing it. Tricky paragraphs could take whole days. I’d read and re-read them over and over, changing words and tweaking commas while ruining my kidneys with Diet Coke and testing the patience of my long-suffering girlfriend (thankfully now my wife and the mother of my children).

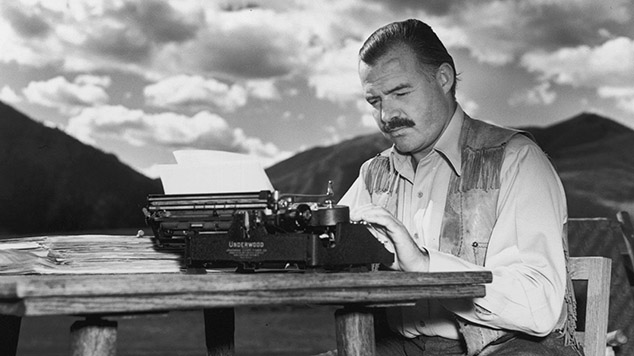

I didn’t look this elegant

Sit at Your Chair and Bleed

My next book was even harder. I wrote the first draft in a couple of weeks and then spent four years rewriting it. One particular chapter took an entire year. Nevertheless, I kept my head down and finally finished the damned thing. Then I was struck by an awful realisation: the better I got at writing, the harder it became. This is something the narrator of my novel, Mervyn vs. Dennis, discusses:

Writing works backwards. The better you get, the harder it is. I missed how I wrote when I was eight. I’d sit down and splurge and love every word, absurd little stories that made little sense. Now I spent half my time sweating about passive voice and dangling participles. I’d fret and I’d fuss over each precious word then come along a month later and bin the whole chapter. I knew this was the graft to make fiction flow but sometimes it felt like the wrong way around.

I was terrified about the future. If I kept getting better, writing would keep getting harder. It would get to the point where writing became so hard that I’d never be able to write at all.

Bleed, dear boy, bleed!

Escaping the Skill Plateau

At the time, I didn’t know there was a skill plateau. I honestly thought I was doomed. My own standards had become so cripplingly high and writing itself had become so hard that a lot of the pleasure of writing was lost. I’d put so many years into writing, at the expense or learning other skills, that I couldn’t simply give up on the only thing I seemed half-decent at. But the prospect of writing another book was so daunting that I couldn’t face it. Having just written a dark, complex thriller, I decided to write something light and easy. That’s where Mervyn vs. Dennis came from. Although it has many dark moments, it was a genuine pleasure to write, and much easier than my previous book. This time, I edited as I wrote, managing a steady 500 words per day. I finished the book in 9 months.

Despite being easier to write, I still spent a lot of time rewriting and editing. Those chunks of 500 words that I wrote and edited every day were several hours of work each. Nevertheless, I wrote an entire novel in under a year compared to writing a single chapter in a year. Having said that, I never had a moment like I did recently while writing Grand Theft Octo. I have never had a moment where I managed to write 500 words that required almost no editing whatsoever. So what has happened to me? Why am I finally able to write at a reasonable pace without feeling like I’m bashing my head against a wall? It’s something I’ve thought a lot about lately, and I have a few possible answers.

Beyond the Skill Plateau

The cynical answer is that my standards have slipped. I used to labour over my craft and now I churn out books without quality control. The problem with that theory is I think my writing is better than ever. I’m currently working on a dark fantasy novel and it’s the best stuff I’ve ever written. So if my standards haven’t slipped then what on earth is going on? I think, after countless years of toil and suffering, I’ve finally escaped the skill plateau. I’m not saying that I’ve mastered writing. I want to keep improving. But now I can write and edit much more efficiently. I’m no longer wandering in the dark. I know much better now what works and what doesn’t.

There are, of course, still moments when I bash my head against the wall. In that past, I would have been stuck for weeks but now all it takes is a contemplative walk or pensive shower. I now see 500 edited words per day as my absolute minimum. If I don’t have any freelance work from my day job, I can manage 1000 words. Once upon a time, that was unthinkable. Right now, not only do my first drafts need less work than they used do, but my editing process is so much more focused and efficient that it no longer feels like an uphill struggle. That allows me to look beyond the minutiae of the words themselves and focus even more on storytelling and character.

Never Give Up Hope

If you’re suffering in a skill plateau of your own, I have one message for you: there is hope. It won’t last forever. What you’re doing right now is improving. It might feel like a never-ending struggle but what’s really happening is that you’re becoming a better writer. All those hours you spend contemplating a tricky sentence aren’t wasted at all. They’re all part of your journey to improve your craft. So, keep on suffering, but always remember that it won’t last forever. There’s a chance, of course, that another skill plateau is heading my way. If that happens, hopefully I’ll be able to follow my own advice.